One sample from a scoop of clay.

One sample from a

scoop of clay.

Sometimes you just have to take Paleontology into your own hands.

That was my conclusion after years of trying to find a paleontologist who could identify a "new" fossil I had found. Yes, I went to the geology library at the University of Cincinnati and combed through hundreds of professional papers dealing with phosphate fossils and the stratigraphy of the Cincinnatian Series. I did learn a great deal about Cincinnati paleontology. Having a mystery fossil really pulls you in. I recommend understanding your ignorance to anyone who wants to learn more. I'm an amateur. Actually I'm a fossil enthusiast.

In these pages I'll talk about a phosphatic microfossil I refer to as my "Mystery Fossil." The identity of the fossil is now clearly known. It's the phosphatic mold of the surfaces of bivalve hinge teeth. From multi-plate elements of the "Mystery Fossil" it appears to have come from Lyrodesma sp. I'll take you through my discovery process in finding and identifying this "Mystery Fossil." It was quite an adventure and learning experience. These pages have been written and modified over a period of 15 years. So you will find some inconsistencies in what I've written. The photography is not the best. Most were taken by holding my camera to the lens of my microscope.

This mystery microfossil ranges in size from 0.5 mm to 2 mm long. I first found this in Florence, Kentucky. My first deduction about it's identity is that it is likely to be a partial phosphatic mold because it is only found in the phosphatic "Cyclora Fossil Hash" layers of the site from the Middle to Upper Arnheim Formation of the Cincinnatian (Upper Ordovician). That deduction turned out to be right. I've learned, though, to never be so committed to your initial conclusions that you are unwilling consider other people's ideas. It was these ideas that challenged me to find the true identity of these abundant but unknown microfossils.

I am a member of the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers, our local fossil club. At each meeting are numerous professional paleontologists. I showed the professionals my mystery specimens.They could not identify the fossils other than to say they are part of the "Cyclora Fauna," and recommended Miami University Anthony Martin's masters thesis on the subject). These guys are my mentors (Dr. David Meyer, Dr. Richard Davis, Dr. Carlton Brett, Dr. Colin Sumrall). They were able to recommend experts for me to consult. In particular, there was hope that my ridged mystery microfossil could actually be micro-vertebrate material from the Late Ordovician Period. It's considered by some to be the holy grail of Cincinnati fossils.

Since I had found thousands of these tiny phosphatic fossils from dissolved clay, I was able to send specimens to paleontologists from around the world specializing in different types of fossils to see if they know what this is. Their responses were consistently that they had not seen this before and did not know what it was. But they told me what it's not and gave me lots of ideas as to what it could be. It was up to me to investigate each possible identity and determine if it's correct or not. From that, I was able to determine that my phosphatic mold was formed from the grit between the dentitions (teeth) on the hinge of a bivalve, possibly Lyrodesma sp..

While a partial mollusk mold is not the holy grail micro-vertebrate fossil, it did open the doors for paleontologists at IPFW and UK to disprove the commonly accepted notion that these phosphatic "Cyclora Fauna" were dwarfed by environmental conditions while alive. My "mystery" bivalve hinge dentition molds were clearly from full-sized clams - at least what is considered full-sized in the Late Ordovician Period.

The mystery fossil is abundant in a couple of fossil hash layers on the site in Florence, Kentucky. A 2, 3 or 4-plate specimen can be found on every rock you pick up and samples of the gritty soil taken home in bag and cleaned will yield dozens of single and double plate specimens.

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

General Description of Exterior Structure

Some Four-plate Specimens

Speculation on the Identity of the Mystery Fossil

Description of Layer Containing the Mystery Fossil

Pictures of 3, 4, and 6-plate specimens

See a stereo image of a 4-plate specimen

Click here to see THIN SECTIONS of the Mystery Fossil

The Bivalve Hinge Teeth Hypothesis

Photos of Lyrodesma dentations resembling Mystery Fossil

Possible Evidence of Secondary Phosphatization and Origin of the Nodules in the

Mystery Fossil

The Mystery Fossil is Informally Identified in 1972

Bill Harrison

How to Determine the Clam

(Lyrodesma sp.) Valve Size from Phosphatic Molds of Dentitions (the Mystery

Fossils).

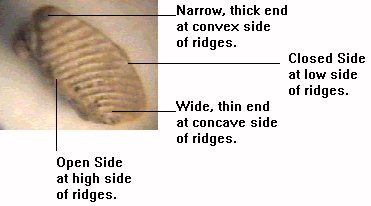

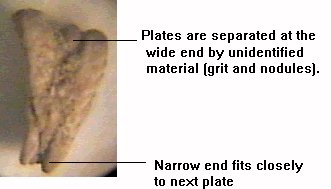

There seems to always be an end that is open, exposing grit, nodules and possible bridges between the plate sides. It is always the same end that is open. The opposite side of each plate is a mirror image of the first side. One "facing" side of each plate has the high end of the ridges on the left and the other side has the high end of the ridges on the right. We can refer to the facing sides as the "high on left" side and the "high on right" side. It seems to me that the open end (the end with guts showing) is always on the "high side" of the ridges. This leads me to wonder if the open side of each specimen is incomplete, perhaps because the shell becomes too thin to be preserved. When there are two plates stuck together, both plates have their ridges oriented the same way. They are usually closer to each other on the wide, thin end as shown below.

There appears to be grit and nodules between attached plates. This may have been material belonging to the living animal. Some plates appear to be slightly bowed in one direction as shown above, while others appear to be relatively flat.

Some plates are much wider than others, as if serving the purpose of two normal plates. These have an additional curved bottom as shown above. Perhaps this curved around another body part to which it attached. It is possible that this wide plate is complete, while all the narrower plates you find are simply broken versions of this wide, complete plate.

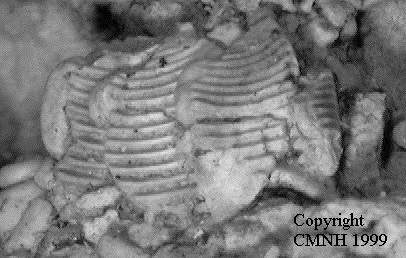

Here is a four-plate specimen in matrix. In this example, some of the plates are equidistant to each other for the entire length of the plate. There is black material between the plates with a few light colored objects bridging the plates.

Here is another four-plate specimen in which the plates are offset from each

other. The fourth plate is broken (right). Note the nodules hanging out the left

side of each plate.

Photo compliments of Colin Sumrall, Cincinnati Museum Center.

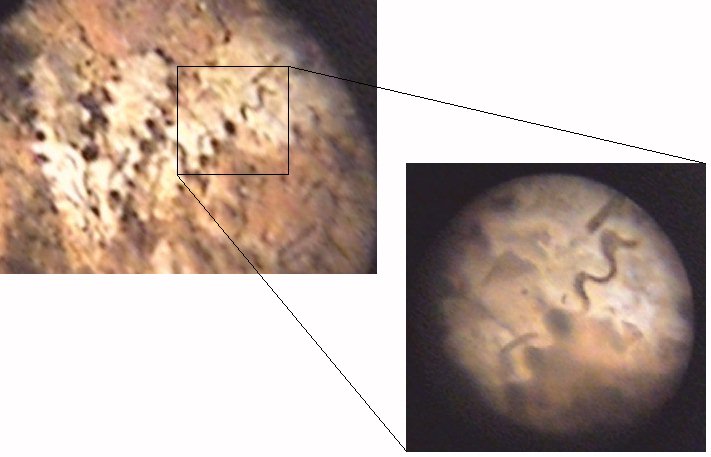

Specimen 13

Shows how the plates fit together. This appears to be a juvenile specimen. It is

smaller than most and the ridges form a sine-wave curve as illustrated at right.

I have shown it to many experts and no one had recognized it or was even sure what class it is in. Some people have ruled out Echinoderm because, when broken, it doesn't exhibit a stereom structure of pores. It could have been a Cirrepedia, but experts have ruled out Machaeridian. The problem there is that the shell of a Machaeridian is thin. This mystery microfossil is thick, but may well be a mold. It could have been an Operculum (foot plate) of a gastropod. The problem is that there is no gastropod in this layer the right size to have this sized operculum. Another problem is that the ridges look the same on both sides. An operculum would not have ornamentation on both sides. It could be a part from an Ordovician fish. Again, the problem is that the ridges look the same on both sides, which is uncharacteristic of fish parts.

I had thought that perhaps this mystery fossil could be a bryozoan colony internal mold. The abundant bryozoans from this site are preserved as internal molds. In this form, the zooids form rods. The overlying mesh pattern is removed. The mystery plates could be where the phosphates have melded the zooids together. Phosphates have been found at this site oozing into and out of any opening available.

Another good possibility that turned out to be the right answer is that of pelecypod hinge teeth. The Upper Ordovician clam, Lyrodesma, has teeth that closely resemble the multiple plate specimens of our mystery fossil. In this case, each mystery plate would be the mold of phosphates between the individual teeth of a single valve.

Click Here for a detailed description of my pelecypod hinge teeth hypothesis .

Click Here for some photos of Possible Evidence of Secondary Phosphatization and Origin of the Nodules in the Mystery Fossil

The mystery fossil comes from a layer in the middle of the Arnheim Formation in the Cincinnatian Series of Northern Kentucky. It can be described as "fossil hash with Cyclora gastropods". This 1 foot layer consists of sandstones and loose sand material. The sandstone is comprised of a reddish brown gritty matrix filled with tiny gastropods, pelecypods, bryozoans, annelid worm tubes, cyclocystoid plates and other unidentified plates which all appear as white dots in the matrix when first coming across such rock.

The gastropods and bryozoans are white to yellow in color. The gastropods appear to have a coating of brownish/blackish material, perhaps contributing to their yellowish coloring. The mystery plates, similarly, vary in color from white to yellow and possess a brownish black grit coating.

The quantity of Cyclcocystoid plates in this "fossil hash" is astounding. They are very abundant and ubiquitous throughout this layer. The "mystery fossil" is also ubiquitous in this layer but only slightly abundant. One specimen of the "mystery fossil" can be found on the surface of almost every rock in the layer.

Other types material found in this sand and matrix include a conodont and a scolecodont. Some crinoid stem and cup plates are also found. Echinoderm material has the stereom structure filled with phosphates, which can be seen when broken or dissolved in acid.

Removal of samples of the loose sand surrounding the "fossil hash" rocks has yielded many specimens of the mystery fossil free from matrix. Almost half of the specimens found are double-plate specimens. A couple of three-plate specimens have been found loose, but many more three-plate examples have been found imbedded in the surface of the rocks. To date, 20 four-plate specimen have been found on the surface of rocks.

The layer containing this fossil hash is just above a one-foot-thick limestone hard layer consisting almost entirely of Rafinesquina Brachiopod fragments. Similar layers of badly fragmented Rafinesquina can be found above the "fossil hash" layer.

Other layers above the "fossil hash" layer include shale with zones of very abundant Zygospira Brachiopods. There are other gastropod zones consisting of larger specimens including Cyclonema . Fragments of the trilobites Isotelus and Flexicalymene have been found in these shale layers as well as one complete Flexicalymene.One such shale layer of abundant Zygospira Brachiopods exists immediately above the "fossil hash" layer.

Here's a group picture showing just how common these mystery fossil are. They

were picked out of the sand with a tweezers.

More info on the layer in which this "mystery fossil" was found:

Introduction to Cyclora Fossil Hash

Discussion of the Echinoderm preservation in this layer

Other Fossils found in the Cyclora Fossil Hash layer

Site DescriptionPictures of 3, 4, and 6-plate specimens

See a stereo image of a 4-plate specimen

Click here to see THIN SECTIONS of the Mystery Fossil!

The Pelecypod Hinge Teeth Hypothesis

Possible Evidence of Secondary Phosphatization and Origin of the Nodules in the Mystery Fossil (NEW)